In the mid-1800s the Midwest was on the frontier of America. That remoteness, combined with the fact land was less expensive than on the East Coast, offered groups with new and varying religious beliefs a welcome sanctuary and testing ground for their version of a perfect society.

In his book “Utopian Communities of Illinois,” Randall J. Soland refers to the area as “heaven on the prairie,” implying this was the perfect religious refuge where different beliefs might flourish and be practiced without interference.

Most of the attempts at utopian communities dissolved fairly quickly. Yet over time several near St. Louis that began in the early to mid-1800s have surprisingly become tourist destinations featuring visitor centers, tours of remaining historic buildings and festivals tied to the original heritage of the communities held throughout the year.

Here are five utopian communities near the St. Louis metropolitan area that would make a nice mini vacation.

The Colony Hotel in Bishop Hill dates to 1852.

Bishop Hill, Illinois

People are also reading…

“This was the destination of the first mass migration of Swedes to the United States,” says Bryan Engelbrecht, the site services specialist at the Bishop Hill State Historic Site. “After they arrived, letters they wrote to their relatives started an influx of Swedes that lasted from 1850 to the beginning of World War I.”

Located 45 miles northwest of Peoria, the settlement was the result of a religious movement led by Swedish pietist Eric Jansson emphasizing personal faith against the teachings of the Swedish Lutheran Church. An example of his preaching in conflict with the state church was the church’s belief that a true Christian is without sin and even unable to sin.

When Jansson began to be repeatedly imprisoned, released and imprisoned again, he sent a trusted follower as an emissary to the United States to find a suitable location where he and his followers could set up a utopian community centered around their religious beliefs.

In 1846 as many as 1,200 Janssonists left their Scandinavian homes and settled in Illinois, where they named their new community Bishop Hill after Jansson’s Swedish birthplace of Biskopskulla. Under Jansson’s direction Bishop Hill was a commune, with everyone selling their assets and pooling their resources into a common treasury.

After a difficult start when one immigrant boat disappeared at sea and a fourth of the colonists died from disease, the colony began to thrive under Jansson’s leadership.

“Land owned or leased by the colony grew to 14,000 acres,” Engelbrecht says, “and by 1849, the commune had constructed a flour mill, two sawmills, a three-story frame church and various other buildings. At the peak population there were 700 Janssonists living here, producing agricultural goods, fine linen, furniture, wagons and brooms.”

Jansson died in 1850, and management of the commune passed to a seven-member board, but by 1855 members began to question the debt the colony had amassed due to investments that proved to be worthless. Talk of dissolution began as early as 1858, and by the early 1860s assets had been divided among members and the colony ceased to exist.

“The last known reference of someone practicing the Janssonist religion is 1880,” Engelbrecht says. “Of the 130 residents still in Bishop Hill, about 25 are descendants of the original settlers.”

However, the memory of the Janssonist community remains strong. In 1896 Old Settler’s Day was organized to celebrate the colony, and it has continued to be celebrated the second Saturday of every September.

About 85,000 people visit yearly, with several arriving from Sweden where the colony is still recognized as an important part of Swedish history.

In 1961 the Bishop Hill Heritage Association was formed when a small group of descendants met and resolved to preserve their Swedish heritage and protect the 14 remaining historically significant buildings, including the 1854 Steeple Building with its three-story clock tower.

A museum houses early village artifacts and a valuable collection of 106 folk art paintings by original colonist Olof Krans, who arrived in 1850 at the age of 12. In 1896 he began painting memories and people from his youth, which effectively document the everyday life in the early days of the colony.

More info • Visitbishophill.com

The Roofless Church in New Harmony, Indiana, was commissioned by Jane Blaffer Owen, the wife of a descendant of Robert Owen. Architect Philip Johnson designed the church, and it was completed in 1960. The curved dome is a protective cover for a sculpture.

photo by Pat Eby

New Harmony, Indiana

This picturesque village nestled alongside the Wabash River has the distinction of having been the site of two attempts at utopia.

The first group, known as the Harmony Society, was founded in the 1780s by Johann Georg Rapp and his adopted son, Frederick. Holding Anabaptist beliefs rejected by the Lutheran church, the Harmonists emigrated from Württemburg, Germany, to the United States in 1803, seeking religious freedom.

Claire Eagle, the interim assistant director of Historic New Harmony, says “members lived communally, pledging to put the needs of their society above all else. In return, the members were to receive food, shelter and care if they remained with the group.”

With the first purchase of 3,000 acres in Butler County, Pennsylvania, a community named Harmony was established, only to move to the Indiana Territory 11 years later when Pennsylvania land became too expensive for expansion, and population growth eliminated the isolation they desired.

Purchasing 20,000 acres in 1814, about 700 Harmonists built a new town in the wilderness in Native American territory in what is now southern Indiana.

The society submitted to spiritual and material leadership under Rapp and worked together for the common good of all its members. Believing that the second coming of Christ would occur during their lifetimes, the Harmonists were content to live simply under a strict religious doctrine. They gave up tobacco and advocated celibacy.

Although profit was not a primary goal, under the guidance of Frederick the economy grew gradually from one of subsistence agriculture to diversified manufacturing. “They succeeded in creating a thriving economy, selling surplus goods as far as Europe and became known for their rope, whiskey and fine cloth,” Eagle says.

While the enterprise was profitable it was not sufficient to carry out planned expansions. In 1824 the Harmonists decided to sell their Indiana property and return to Pennsylvania. There they reached their peak of prosperity in 1866, but the practice of celibacy and several schisms thinned the society’s ranks, and the community was eventually dissolved in 1905.

Robert Owen, a Welsh industrialist, social reformer and idealist purchased the town of Harmony in 1825, and renamed the village New Harmony. Owen’s intention was to create “a new moral world” of happiness, enlightenment and prosperity through education, science, technology and communal living.

The community dissolved quickly, ravaged by personal conflict and inadequacies in labor and agriculture, but the efforts of this utopian experiment brought advancement in scientific and educational theory and practice, as well as changes in social thought, Eagle says.

While the Owenite social experiment was brief, the community developed ideas that changed American society. It created one of the first kindergarten schools, the first trade school and the first free library in the United States.

Today, sprinkled among a cluster of boutique stores, restaurants and bed-and-breakfasts there are 30 structures from the Harmonist and Owenite utopian communities that remain as part of the New Harmony Historic District, also a National Historic Landmark.

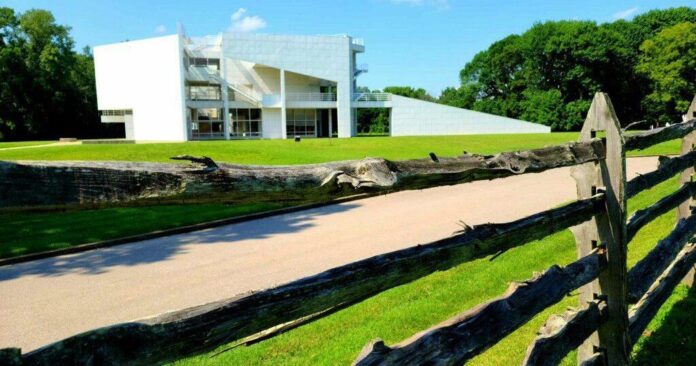

In contrast to the historical buildings remaining, an ultra-modern Visitors Center on the edge of the community designed by architect Richard Meier is usually the first stop for visitors.

More info • visitnewharmony.com

Children dressed as Dutch dancers celebrate the founding of the town in 1847 during the annual Tulip Time Festival.

Pella, Iowa

“Several factors led to a group of Dutch settlers departing the Netherlands in the spring of 1847 and eventually settling in Pella,” says Valerie Van Kooten, the executive director of the Pella Historical Society and Museums. “They did not have a theological difference with the Dutch Reformed Church, the state church of the Netherlands, but strongly disagreed with the government directing when and where they could preach, and how much money should be sent from the church to the government. It was also a period of poverty and high taxes and an overall dissatisfaction with life there at the time.”

Led by the Rev. Hendrik Pieter Scholte, who had a disregard for ritualism and authority, a group of 800 followers signed a Secession Agreement with the church and set sail for America in four ships.

Historical records show the ship’s cleanliness was not to Dutch standards. Almost immediately the group cleaned the ships from top to bottom. Later the ship captains testified that they had never brought “a more orderly or better-behaved people across the Atlantic.”

Scholte’s followers briefly stayed in St. Louis, while he and several members of the group scouted Iowa as a new permanent home, where they purchased 33 farms owned by settlers already living in the area. Three months later all the immigrants arrived at their new home in the wilderness, greeted by a pole with a sign on top that read “PELLA,” named after a city in modern-day Macedonia where Jewish followers of Jesus fled for refuge before the Romans destroyed Jerusalem.

“They established the Christian Church with very much the same beliefs of the religion they left, but with a lot more freedom to worship as they liked,” Van Kooten says. “When Scholte died in 1868 the town was thriving, but without his leadership the colony drifted back to the Reformed Church.”

Today many members of the community are direct descendants of the original Dutch families. “When there were still phone books, surnames beginning with the letter ‘V’ filled six pages,” Van Kooten remembers.

A block in Pella in what is known as the Historical Village contains 23 original and reproductions of buildings from the 1850s. Nearby is the original home of Scholte built in 1848. In 2001 a fully functioning 1850s style windmill made in the Netherlands was reassembled in the village. Standing 124 feet high it is the tallest working windmill in North America.

“The first full weekend each May (May 5-7 in 2022) we have the Tulip Time Festival to celebrate our Dutch heritage,” Van Kooten says, noting that 250,000 people visit the town of 10,000 over a three-day period. In 2010 a world record was set for the most people dancing in wooden shoes when 2,600 people danced for more than six minutes.

Part of the town’s Dutch heritage incudes Peter Kuiper, a member of the Reformed Church who founded the Pella Corporation, the maker of Pella windows and doors, in 1925.

Town history also includes Wyatt Earp who lived in Pella from the age of 2 until 16 when the family moved farther west. The archives of the town paper mention Earp got into a fight with some of the local immigrants and was hit in the head with a wooden shoe.

More info • Visitpella.com/visitorsguide

The general store in the village of High Amana remains largely unchanged from 1857.

The Amana Colonies, Iowa

The history of Amana Colonies begins in 1714 in the villages of Germany and continues today on the Iowa prairie. Then a belief that God may inspire individuals to speak became known as the Community of True Inspiration.

By 1843 persecution of the group along with economic depression in Germany, forced the community to begin searching for a new home. Community members pooled their resources and purchased 5,000 acres near Buffalo, New York.

By 1855 more farmland was needed, and less expensive land was found in Iowa where the new settlement was named Amana, a name taken from the Song of Solomon 4:8, which means to “remain true.”

Instead of one large commune, the colony was initially established as six separate villages spread over 26,000 acres in an Iowa river valley. Each village was only a mile or two distant from the neighboring town. The names, most of which clearly designated their location, were Amana, East Amana, West Amana, South Amana, High Amana and Middle Amana. Homestead village was added in 1861, giving the colonies access to the railroad.

Dissolution occurred in 1932 due to a belief that communal life was a barrier to achieving individual goals. Perhaps the best-known success of the move toward independent ownership was Amana Appliances founded in 1934 in Middle Amana by George Foerstner when he was challenged by a local businessman to build a reliable commercial beverage cooler.

The successful product led to the making of refrigerators for butchers. In 1947 Amana manufactured the first upright freezer for the home, and continued success led to a variety of home appliances manufactured under the Amana name.

Declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965, today many of the original brick, stone and clapboard buildings remain in each of the seven villages. A ride among the villages, stopping at the various small businesses along the way, makes for a very pleasant afternoon.

More info • Amanacolonies.com

Visitors tour the old town of Nauvoo with the aid of Percheron draft horses Blue and Sky.

Nauvoo, Illinois

For 20 years from the early 1840s until about 1860 Nauvoo was the center of two experiments in religious political communitarianism. First were the Mormons, followed by a religious sect from France.

Today the village is a tourist destination for Mormons and others who come to learn about the town’s religious history and visit the museums and 30 surviving historic brick homes and businesses. A visitor center helps orient guests, and guided tours are free.

Unlike the other Midwestern religious communities mentioned in this article the Mormon religion traces its origins from the early 1800s in the United States, not Europe.

By the mid-1840s the religion was well-established. But persecution like that experienced by European religious immigrants led Mormon church leaders to purchase land in what was then the small town of Commerce, Illinois, hoping for sanctuary and the freedom to practice their beliefs as they wished.

Soon there were enough Mormons in Commerce to be able to rename the village “Nauvoo,” a Hebrew word meaning “beautiful place” or “city beautiful.” Nauvoo grew rapidly and for a few years was one of the most populous cities in Illinois.

Most were members of the Mormon Church and with such a majority, Mormon President Joseph Smith reversed the traditional separation of church and state. He was Nauvoo’s mayor and chief judge, newspaper editor and commander-in-chief of the town’s militia.

Soon angry mobs suspicious of Smith’s autocratic control and the introduction of polygamy led the governor to place Smith in jail for his protection. However a mob stormed the jail and murdered Smith on June 27, 1844. By the end of 1846 most of the Mormons had departed on a westward trek to Utah led by Brigham Young.

Then, in 1848 a group of French Icarians left France to form a utopian community on the American frontier and settled in Nauvoo. Led by Etienne Cabet, their philosophy abolished private property and individual enterprise, believing that with all working for the common good the evils of society would disappear.

Their beliefs stressed the importance of conventional marriage, but with important variations. Husband and wife were allotted one room in the community dwelling. All meals were taken in a community dining room, and requests for such items as new clothes were submitted to the community council.

At its peak there were 500 Icarians living in Nauvoo, but the more ambitious quickly tired of working harder without improving their own way of life. By 1860 the group had disbanded, disillusioned with their utopian community.

Today Nauvoo is experiencing renewed attention by the Mormon faith. “The Mormons value the history and spirit of Nauvoo,” says author Soland. “More Mormon retirees and young families who can work remotely are coming to Nauvoo. I believe Nauvoo will once again become a central Mormon community,“ he says.

More info • beautifulnauvoo.com

Stay up to date on life and culture in St. Louis.

Escape the ordinary and discover the extraordinary! From bustling cities to serene landscapes, every journey begins with a single step—let us guide yours. Enjoy curated itineraries, hidden gems, and hassle-free bookings designed for explorers at heart. Whether it's a weekend getaway or a globe-trotting adventure, your Next unforgettable experience is just a click away.